According to Islamic Studies Researchers point of view

Introduction

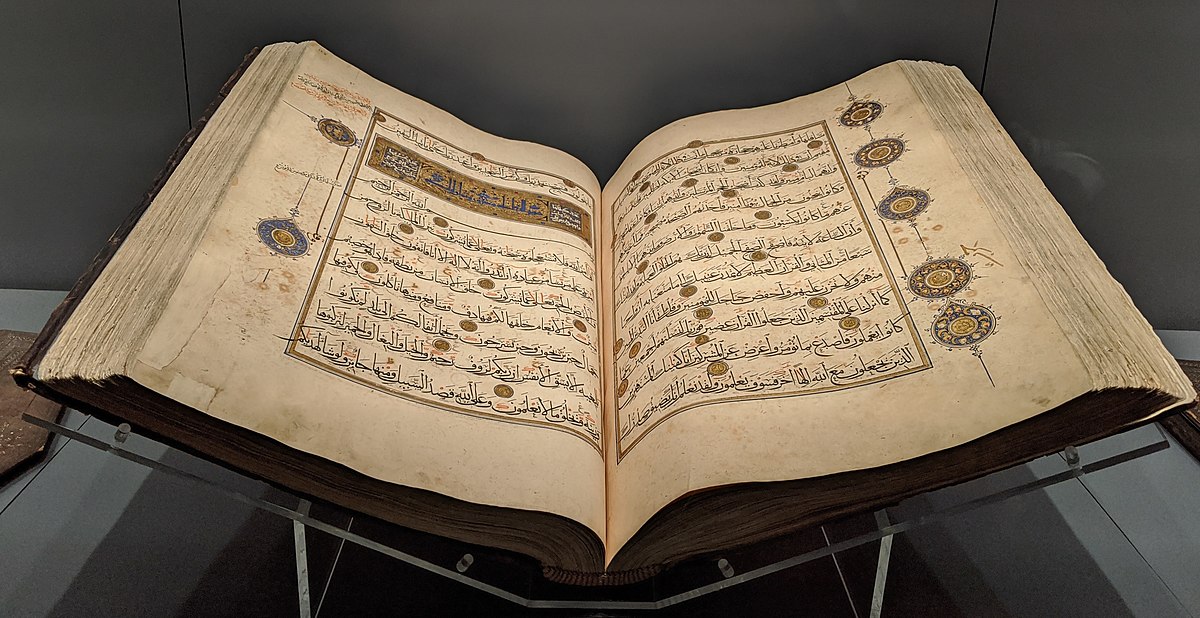

Dhul-Qarnayn, literally (The man with Two-Ramparts) is one of the most enigmatic and debated figures in Islamic scripture. He appears in Surah Al-Kahf (Chapter 18), verses 83–101 of the Qur’an, as a divinely empowered ruler who journeys to the farthest reaches of the earth, establishes justice, and ultimately constructs a massive barrier to contain the chaotic tribes of Yajouj and Majouj (Ya’juj and Ma’juj). While the Qur’an does not explicitly name Dhul-Qarnayn or situate him in a specific historical era, his story has captivated theologians, historians, and archaeologists for over fourteen centuries.

This article explores the Qur’anic narrative of Dhul-Qarnayn, analyzes the theological and symbolic dimensions of his story, and reviews the major historical identifications proposed by scholars — from Alexander the Great to pre-Islamic Persian kings — while also addressing why his identity remains unresolved.

I. The Qur’anic Narrative: Who Is Dhul-Qarnayn?

The story of Dhul-Qarnayn is recounted in Surah Al-Kahf as part of a divine response to questions posed to the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ by the Quraysh, likely under the prompting of Jewish scholars in Arabia. The Qur’an presents him as:

Verily We established his power on earth, and We gave him the ways and the means to all ends. 84 - Al-Kahf.

He travels westward to where the sun sets (into a muddy spring), eastward to where it rises (over a people with no shelter), and finally northward to a mountain pass between two mountains, where he encounters a people oppressed by Yajouj and Majouj. With their help and divine permission, he constructs a rampart of iron and molten copper — a barrier that will hold until the appointed time of divine reckoning.

Key theological themes:

- Divine empowerment: Dhul-Qarnayn is not a prophet, but a righteous ruler granted authority by God.

- Justice and monotheism: He refuses to oppress people, offers them fair terms, and attributes his success to God.

- Eschatological symbolism: The barrier he builds is temporary; Yajouj and Majouj will break free near the Day of Judgment (Qur’an 21:96).

The Qur’an deliberately avoids naming him or anchoring him to a specific dynasty, inviting reflection rather than historical cataloging.

“Dhul-Qarnayn” literally means “Possessor of Two Ramparts.”

II. The Name “Dhul-Qarnayn”: Literal and Symbolic Meanings

The epithet “Dhul-Qarnayn” literally means “Possessor of Two Ramparts.” Several interpretations have been proposed:

1. Symbol of Power: In ancient Near Eastern iconography, Ramparts symbolized strength and kingship (e.g., Mesopotamian bull imagery, horned crowns of deities and kings).

2. Geographical Reference: “Two Horns/ Ramparts” may refer to the two extremities of his empire — East and West — which he traverses.

3. Temporal Reference: Some scholars suggest it refers to two epochs or ages he influenced.

4. Mythological Allusion: Horns appear in legends of Alexander the Great, who was sometimes depicted with ram horns (associated with the Egyptian god Amun).

The ambiguity is intentional — the Qur’an emphasizes his function (a just ruler empowered by God) over his identity.

III. Historical Identifications: Who Was Dhul-Qarnayn?

Scholars and historians have long debated Dhul-Qarnayn’s historical identity. Major theories include:

1. Alexander the Great (Iskandar al-Macedoni)

Proponents: Classical Muslim historians (Al-Tabari, Al-Qurtubi), Western Orientalists (Theodor Nöldeke, Montgomery Watt), and popular Islamic tradition.

Evidence:

- Alexander was known in Syriac Christian and Persian lore as “Alexander the Two-Horned,” stemming from his depiction with ram horns (after being declared son of Amun in Egypt).

- The Syriac Alexander Romance (circa 6th–7th century CE) includes a story of Alexander building a gate against Yajouj and Majouj — strikingly similar to the Qur’anic account.

- Alexander’s empire stretched from Greece to India — fitting the “East to West” motif.

Counterarguments:

- Alexander was a polytheist and often brutal conqueror — unlike the pious, God-fearing Dhul-Qarnayn of the Qur’an.

- The Qur’an never calls him “Alexander,” and early Muslims distinguished between Iskandar (Alexander) and Dhul-Qarnayn in some traditions.

- The Qur’anic account may be drawing on the *legend* of Alexander, not the historical figure.

2. Cyrus the Great of Persia

Proponents: Modern scholars such as Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Dr. Shabbir Akhtar, and some contemporary historians.

Evidence:

- Cyrus (r. 550–530 BCE) was a Zoroastrian but known for his tolerance, justice, and liberation of the Jews from Babylon — aligning with Dhul-Qarnayn’s just rule.

- His empire spanned from Lydia (West) to the Indus (East).

- Ancient Persian reliefs depict kings with horned crowns — possibly inspiring “Two Horns.”

- The “two Ramparts” may refer to his dual heritage: Mede and Persian.

- Unlike Alexander, Cyrus is praised in the Bible (Isaiah 45:1 calls him “God’s anointed”) — making him a more plausible monotheistic figure.

Counterarguments:

- No ancient source links Cyrus to Yajouj and Majouj or a northern barrier.

- The Cyrus Cylinder mentions rebuilding temples and freeing peoples, but not constructing a wall against barbarians.

3. Pre-Islamic Arabian or Mesopotamian Kings

Some scholars suggest Dhul-Qarnayn may be a legendary or semi-legendary Arabian king, such as:

- Sa'b Dhu Marathid: A Himyarite king from South Arabian folklore, mentioned in some Islamic sources (e.g., Ibn Hisham, Wahb ibn Munabbih) as having traveled the world and subdued Yajouj and Majouj.

- Nebuchadnezzar II: Occasionally proposed due to his eastern campaigns and biblical notoriety, but lacks the “two horns” motif and righteous portrayal.

These identifications are largely based on regional folklore and lack strong textual or archaeological support.

4. A Symbolic or Composite Figure

Many modern scholars (e.g., Muhammad Asad, Fazlur Rahman, Neal Robinson) argue that Dhul-Qarnayn is not meant to be identified with any one historical figure. Rather, he represents:

- The ideal Muslim ruler: just, powerful, God-conscious, and protective of the weak.

- A literary archetype drawn from multiple ancient legends (Alexander, Cyrus, Mesopotamian heroes).

- A theological device to illustrate divine sovereignty over empires and eschatological signs.

This view aligns with the Qur’an’s tendency to universalize moral lessons rather than fixate on historical personalities.

IV. The Yajouj and Majouj Connection: Myth, History, and Eschatology

Dhul-Qarnayn’s most famous act is building the barrier against Yajouj and Majouj — tribes associated with chaos and destruction in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic apocalyptic literature.

- In the Bible (Ezekiel 38–39), Yajouj and Majouj are associated with northern lands.

- In Syriac Christian tradition, Alexander builds a gate in the Caucasus (often identified with the Caspian Gates or Derbent in modern Dagestan).

- Muslim geographers (e.g., Al-Idrisi, Yaqut al-Hamawi) located the barrier in Central Asia or the Caucasus.

- Modern speculation ranges from the Great Wall of China to ancient Sasanian fortifications in Derbent.

Archaeologically, the Sasanian-era walls of Derbent (in modern Russia), built to defend against northern nomads (Huns, Khazars), are often cited as possible inspirations for the Qur’anic barrier. However, these were constructed centuries after Alexander and possibly after the Qur’anic revelation.

Theologically, Yajouj and Majouj are not merely historical tribes but symbols of moral and social chaos — their eventual release is a sign of the End Times.

V. Scholarly Consensus and Contemporary Views

There is no definitive scholarly consensus on Dhul-Qarnayn’s identity. However, trends in modern Islamic and academic scholarship show:

- Shift away from Alexander: Many contemporary Muslim scholars reject the Alexander identification due to his pagan character and the Qur’an’s moral tone.

- Rise of Cyrus theory: Especially among reformist and historically-minded Muslims, Cyrus is seen as a better fit theologically and ethically.

- Emphasis on symbolic meaning: Increasingly, scholars treat the story as parabolic — meant to teach justice, divine providence, and the limits of human power.

- Interdisciplinary approaches: Archaeologists, historians of religion, and Qur’anic exegetes now collaborate to understand the story’s origins in Late Antique milieu — a world saturated with Alexander legends, Persian imperial memory, and apocalyptic literature.

VI. Theological and Moral Lessons

Regardless of historical identity, the Qur’anic story of Dhul-Qarnayn offers timeless lessons:

1. Power is a Trust from God: Dhul-Qarnayn acknowledges that his means and authority come from God — a model for Muslim rulers.

2. Justice Over Might: He offers people the choice of fair punishment or fair reward — no forced conversion or oppression.

3. Humility in Success: He never boasts; he says, “This is a mercy from my Lord” (18:98).

4. Temporary Solutions: The barrier is not eternal — only God’s decree is. Human efforts, no matter how grand, are provisional.

5. Eschatological Awareness: The story reminds believers that chaos (Yajouj and Majouj) will return — moral vigilance is essential.

VII. Conclusion: The Enduring Mystery

Dhul-Qarnayn remains one of the Qur’an’s most fascinating enigmas. While historical detective work continues — from the ruins of Derbent to the tablets of Persepolis — the Qur’an’s silence on his identity may be its most profound message: it is not who he was, but what he represents.

Whether he was Cyrus, Alexander, a forgotten Arabian king, or a divinely crafted archetype, Dhul-Qarnayn stands as a monument to righteous power — a ruler who journeyed to the ends of the earth not for conquest, but for justice; not for glory, but for God.

In an age of empires, walls, and global chaos, his story resonates more than ever.

Further Reading:

- The Qur’an, Surah Al-Kahf (18:83–101), multiple translations (Pickthall, Yusuf Ali, Abdel Haleem, Mustafa Khattab)

- Al-Tabari, Tarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk (History of the Prophets and Kings)

- Southgate, Minoo S., “Cyrus the Great and Dhul-Qarnayn”, Iranian Studies Journal

- Van Bladel, Kevin, The Alexander Legend in the Qur’an 18:83–102 (Cambridge University Press)

- Asad, Muhammad, The Message of the Qur’an (Commentary on Surah Al-Kahf)

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said, The Qur’an and the Bible: Text and Commentary (Yale University Press).

Dear Visitor; Please take a look at the list of 50 most visited websites in the world wide web: YouTube, Facebook, google, translate, gmail, weather, amazon, Instagram, cricbuzz, Hotmail, wordle, satta king, twitter, yahoo, yandex, sarkari result, Netflix, google maps, yahoo mail, roblox, whatsapp, NBA, BBC news, outlook, pinterest, flipkart, eBay, omegle, live score, tiktok, canva, ipl, premier league, hava durumu, ibomma, walmart, twitch, ikea, shein, linkedin, home depot, e devlet, lottery, snaptik, cricket, serie , nfl, spotify, fox news, amazon prime; There is no book publishing related or project management website in this list. We are working hard to bring these important issues to the center of concentration of societies. Please introduce us via social media, share our website with others and help us to make our world a better place to live. Best Regards.

Write your review