Throughout history, the relationship between Muslims and Jews has been characterized by complex dynamics, but there exists a remarkable and often overlooked legacy of cooperation, mutual respect, and shared prosperity that spanned centuries. While contemporary narratives often focus on conflict, a deeper examination reveals periods of extraordinary collaboration that profoundly shaped the development of both communities and contributed significantly to human civilization.

The Foundation: Early Islamic Period

With the emergence of Islam in the 7th century, a new framework for interreligious relations was established. The Constitution of Medina, drafted by Prophet Muhammad in 622 CE, created a multi-religious community (ummah) that included Jewish tribes as equal members with rights and responsibilities. This document recognized Jews as a distinct religious community with autonomy in personal law and religious practice.

Under Islamic rule, Jews were granted the status of "dhimmi" (protected people), which provided security of life, property, and freedom of worship in exchange for a special tax (jizya). While modern perspectives sometimes critique this arrangement as hierarchical, in historical context, it often represented significant protection compared to the treatment of religious minorities in other contemporary societies.

The Golden Age of Al-Andalus

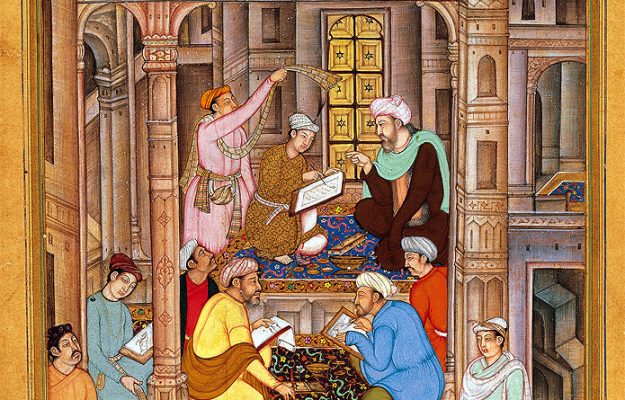

Perhaps the most celebrated period of Muslim-Jewish harmony occurred in medieval Spain (Al-Andalus) from the 8th to 15th centuries. Under relatively tolerant Muslim rulers, particularly during the Umayyad Caliphate and subsequent taifas (petty kingdoms), Jewish culture experienced a renaissance unparalleled elsewhere in the diaspora.

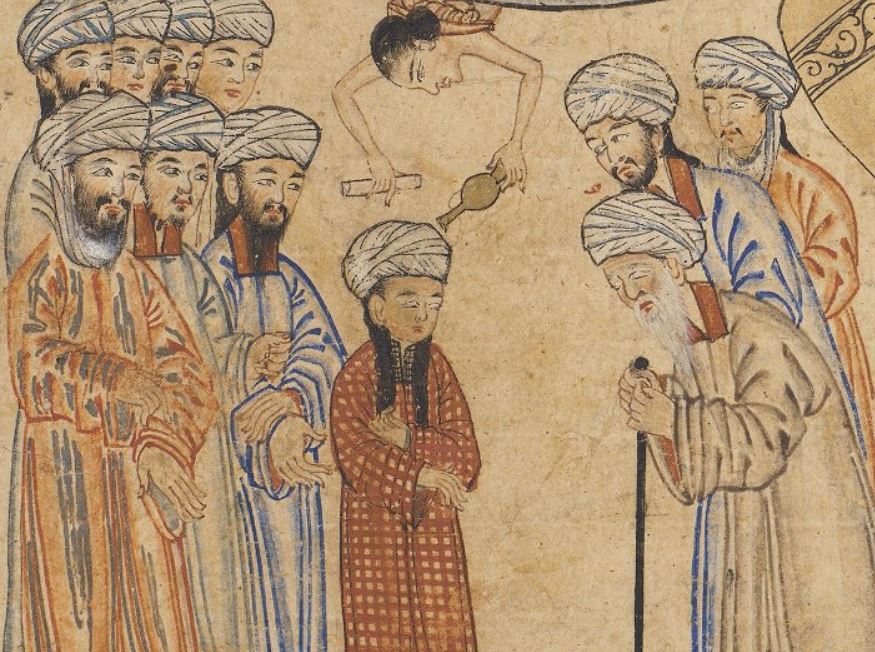

Jewish scholars rose to prominent positions in Muslim courts. Hasdai ibn Shaprut (915-970 CE) served as foreign minister to Caliph Abd al-Rahman III of Córdoba, conducting diplomacy on behalf of the caliphate while simultaneously leading the Jewish community. Samuel ibn Naghrillah (993-1056 CE), known as Shmuel HaNagid, became vizier (chief minister) to the Muslim king of Granada and commanded the Muslim army, all while producing significant Hebrew poetry and Talmudic scholarship.

Granada became centers where Muslim, Jewish, and Christian scholars collaborated

The cultural flowering of this period was characterized by remarkable intellectual cross-pollination. Jewish scholars like Moses Maimonides (1135-1204 CE) wrote most of their influential philosophical works in Arabic, the language of scholarship. Maimonides' "Guide for the Perplexed," written in Judeo-Arabic (Arabic written in Hebrew script), sought to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy with Jewish theology, drawing heavily on Islamic philosophical traditions. Cities like Córdoba, Toledo, and Granada became centers where Muslim, Jewish, and Christian scholars collaborated in translating ancient Greek texts into Arabic and Hebrew, preserving knowledge that might otherwise have been lost. This translation movement, centered in the Toledo School of Translators after the Christian reconquest, continued the collaborative spirit established during Muslim rule.

The Ottoman Model

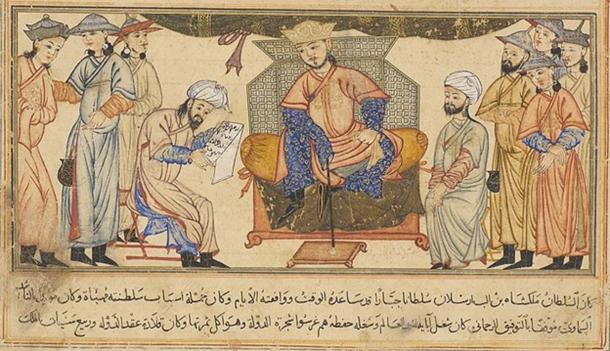

Following the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492, the Ottoman Empire provided refuge to tens of thousands of Sephardic Jews. Sultan Bayezid II famously remarked, "You venture to call Ferdinand a wise ruler, he who has impoverished his own country to enrich mine!" The Ottoman welcome was not merely humanitarian but pragmatic, recognizing the valuable skills Jewish refugees brought in trade, finance, medicine, and diplomacy.

The Ottoman millet system granted significant autonomy to non-Muslim religious communities. Jews were organized as a separate millet with their own religious leadership and legal jurisdiction over personal matters. This system allowed Jewish communities to maintain their distinct identity while participating fully in Ottoman society. Jewish physicians like Joseph Hamon (died 1517) served as personal doctors to sultans, while others held positions as diplomats, financiers, and advisors. Salomon ben Nathan Ashkenazi, for example, represented Ottoman interests in Venice in the late 16th century. In commerce, Jewish merchants often acted as intermediaries between the Muslim world and Europe, facilitating trade and cultural exchange.

Shared Intellectual Pursuits

Beyond politics and commerce, Muslims and Jews engaged in profound intellectual exchanges that advanced human knowledge. In the medieval Islamic world, Jewish scholars like Saadia Gaon (882-942 CE) contributed significantly to Hebrew linguistics and Jewish theology while operating within the Arabic intellectual tradition.

In medicine, Jewish physicians were highly sought after throughout the Islamic world. They studied and advanced medical knowledge preserved and developed by Muslim scholars, building on the works of figures like Ibn Sina (Avicenna). This medical tradition was characterized by empirical observation and clinical practice that influenced European medicine for centuries.

Philosophically, Jewish thinkers engaged deeply with Islamic philosophy, particularly the works of Al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, and Ibn Rushd (Averroes). Maimonides' philosophical writings, deeply influenced by Islamic thought, later became central to European scholasticism through Latin translations.

Economic and Social Cooperation

Economic interdependence often fostered stable relations between Muslim and Jewish communities. In many Islamic societies, Jews engaged in crafts, trade, and finance that complemented the broader economy. Jewish merchants participated in extensive trade networks connecting the Islamic world with Europe, North Africa, and Asia.

In cities throughout the Middle East and North Africa, Jewish and Muslim quarters were often adjacent, facilitating daily interaction and cultural exchange. This proximity led to shared linguistic traditions, with Jews throughout the Arab world speaking Arabic as their primary language and developing Judeo-Arabic dialects for religious scholarship.

Shared Cultural Heritage

The cultural exchange between Muslims and Jews produced rich artistic and literary traditions. Jewish poetry in medieval Spain adopted Arabic forms and meters, while Hebrew grammarians applied Arabic linguistic methods to analyze biblical Hebrew. Music, architecture, and cuisine also show evidence of mutual influence.

This shared heritage is perhaps most visible in Judeo-Arabic literature, which encompasses religious texts, philosophy, poetry, and everyday documents written in Arabic using Hebrew script. This literary tradition preserved Jewish religious scholarship while simultaneously participating in the broader Arabic cultural world.

Both religions recognize prophets

Factors Facilitating Positive Relations

Several factors contributed to these periods of harmonious coexistence:

1. Shared Abrahamic Heritage: Both religions recognize prophets and traditions common to both faiths, creating a foundation for mutual respect.

2. Islamic Theological Framework: The Quran explicitly recognizes Jews as "People of the Book" and affirms their right to practice their religion.

3. Practical Governance: Many Muslim rulers recognized the value of including talented individuals regardless of religious background.

4. Economic Complementarity: Different religious communities often specialized in different trades and professions, creating interdependence.

5. Cultural Openness: Periods of intellectual curiosity and cultural confidence fostered environments where diversity was valued rather than feared.

Lessons for Contemporary Times

The historical record of Muslim-Jewish cooperation offers valuable lessons for addressing contemporary interfaith tensions. These examples demonstrate that religious difference need not be a barrier to peaceful coexistence and mutual enrichment. They remind us that throughout history, communities have found ways to transcend theological differences to build shared prosperity and advance human knowledge.

The periods of genuine cooperation between Muslims and Jews were not merely exceptions to an otherwise conflictual relationship but represent sustained historical realities that shaped the development of both civilizations. This legacy deserves recognition not as a mere historical curiosity but as a model for how diverse religious communities can work together to build inclusive, prosperous societies.

In an era often marked by division, the golden thread of Muslim-Jewish cooperation throughout history offers hope and inspiration for rebuilding bridges of understanding and respect. It reminds us that our shared humanity and common aspirations can transcend religious difference, creating societies where all can flourish together.

Dear Visitor; Please take a look at the list of 50 most visited websites in the world wide web: YouTube, Facebook, google, translate, gmail, weather, amazon, Instagram, cricbuzz, Hotmail, wordle, satta king, twitter, yahoo, yandex, sarkari result, Netflix, google maps, yahoo mail, roblox, whatsapp, NBA, BBC news, outlook, pinterest, flipkart, eBay, omegle, live score, tiktok, canva, ipl, premier league, hava durumu, ibomma, walmart, twitch, ikea, shein, linkedin, home depot, e devlet, lottery, snaptik, cricket, serie a, nfl, spotify, fox news, amazon prime; There is no book publishing related or project management website in this list. We are working hard to bring these important issues to the center of concentration of societies. Please introduce us via social media, share our website with others and help us to make our world a better place to live. Best Regards.

Write your review