Introduction: The Timeless Wisdom of the Qanat

In the arid heartlands of ancient Persia (modern-day Iran), where rainfall is scarce and surface water evaporates rapidly, a brilliant hydraulic innovation emerged over 2,500 years ago: the Qanat (also known as kariz, foggaras, or khettaras). This subterranean aqueduct system—engineered without pumps or electricity—harnessed gravity to transport groundwater from mountainous recharge zones to arid lowland settlements. Today, as the world grapples with unprecedented water scarcity, climate change, and depleting aquifers, the Qanats stands not as a relic of antiquity, but as a sustainable, low-tech blueprint for modern water security.

This article explores the historical development of Qanats, their global spread, their relevance to today’s water crisis, and contemporary efforts to revive and adapt this ancient technology for the 21st century.

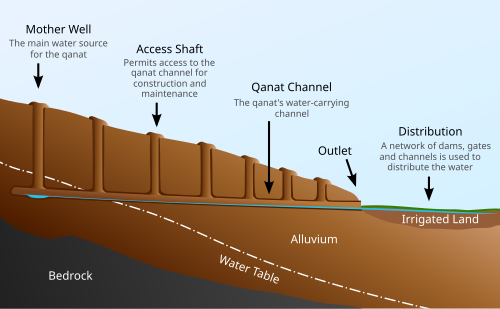

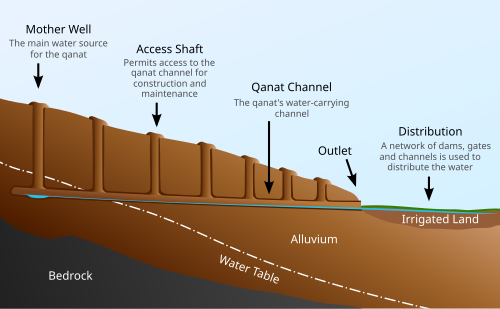

How the Qanat Works: Engineering Genius in Simplicity

A Qanat consists of four key components:

1. Mother Well: Dug deep into an alluvial fan or foothill aquifer to access groundwater.

2. Gentle Inclined Tunnel: A gently sloping underground channel (typically 0.1–0.5% gradient) that channels water by gravity over tens of kilometers.

3. Vertical Shafts: Regularly spaced (20–50 meters apart) access shafts for construction, maintenance, and ventilation.

4. Surface Distribution Network: Channels and canals that deliver water to villages, farms, and public fountains.

The genius lies in its passive operation: no energy input, minimal evaporation (water flows underground), and long-term sustainability if managed properly. Unlike open canals, Qanat lose little water to evaporation or seepage, making them ideal for hot, dry climates.

originating in ancient Iran

Historical Spread and Global Variants

Though originating in ancient Iran around 1000 BCE during the Achaemenid Empire, the Qanat system spread across empires through trade, conquest, and migration.

1. Iran – The Birthplace and Heartland

- Over 40,000 Qanats once supplied water to Iranian cities like Yazd, Kerman, and Kashan.

- The Zarch Qanat near Yazd is the oldest known, dating back over 3,000 years, still functioning today.

- UNESCO recognized 11 historic Qanats in Iran as World Heritage Sites in 2016.

2. Oman – The Falaj System

- Known locally as falaj (plural: aflaj), these systems date back to at least 1000 BCE.

- Three aflaj systems in Oman—Al Ayn, Al Ghail, and Al Jaylani—are UNESCO-listed.

- Used for irrigation and domestic supply; community-managed via strict water-sharing rules (mudawwana).

3. North Africa – The Foggaras

- In Algeria, Morocco, and Libya, the system is called foggara or khettara.

- The Foggara of Ghardaïa (Algeria) sustained desert oases for centuries.

- Built by Berber communities using traditional knowledge passed orally through generations.

4. Afghanistan and Central Asia

- Called kariz or karez, these systems are vital in Herat, Balkh, and Kandahar.

- Estimated 30,000 karez systems existed pre-1970s; many damaged by war and over-pumping.

- Recent rehabilitation projects by UNDP and FAO have restored dozens.

5. China – The “Karez” of Xinjiang

- Introduced via the Silk Road during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE).

- The Turpan Depression hosts over 1,100 karez systems, some over 2,000 years old.

- Still used for irrigation of grapevines and melons in one of China’s driest regions.

6. Spain and the Americas – Islamic Legacy

- Muslim rulers introduced Qanats to Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain) as Qanats or galerías filtrantes.

- Surviving examples exist in Murcia and Granada.

- Spanish colonists brought the concept to Mexico (e.g., Querétaro’s galerías) and Peru (e.g., Nazca region), though few remain functional.

7. India and Pakistan

- Limited use in Rajasthan and Sindh, often called nahr or bawdis, though less systematic than Persian models.

- Revival efforts underway in Jodhpur and Barmer districts.

Why Qanats Are Relevant Today: Solving Modern Water Crises

With 2.3 billion people lacking safe drinking water and over 4 billion facing severe water scarcity for at least one month per year (UN-Water, 2023), conventional solutions—desalination, large dams, piped networks—are often too expensive, energy-intensive, or ecologically destructive.

Qanats tap renewable aquifers sustainably

Qanats offer a compelling alternative:

Modern Problem: Qanats Solution

Groundwater Depletion: Qanats tap renewable aquifers sustainably when flow rates are respected; they avoid over-pumping by design.

High Energy Costs: Zero electricity needed; gravity-fed operation cuts carbon footprint.

Evaporation Losses: Underground flow reduces losses by up to 80% compared to open canals.

Climate Resilience: Less vulnerable to droughts than surface reservoirs; aquifers buffer seasonal variability.

Community Ownership: Traditional management fosters equity, transparency, and conservation ethics.

Low-Cost Maintenance: Repairs require local skills and materials—ideal for rural, under-resourced areas.

Example: In Iran’s Yazd province, Qanats provide 70% of domestic water despite temperatures exceeding 50°C. Meanwhile, desalination plants consume 3–4 kWh per cubic meter—costing far more and emitting CO₂.

Modern Revival Projects: Global Initiatives

Several countries and international organizations are reviving Qanats as part of climate adaptation strategies:

1. Iran – National Qanat Rehabilitation Program

- The Iranian Department of Water Resources has restored over 1,200 Qanats since 2000.

- Integrated with modern hydrogeological mapping and sensor networks to monitor flow and prevent illegal pumping.

- Policy now mandates Qanat protection zones around heritage sites.

2. Oman – Falaj Preservation Initiative

- Government funds training for falaj custodians.

- Digital monitoring systems track water distribution fairness.

- Schools teach falaj history as part of national curriculum.

3. Morocco – Khettara Revival in Draa Valley

- FAO and Moroccan Ministry of Agriculture restored 80+ khettaras between 2010–2020.

- Combined with drip irrigation to increase agricultural yield by 40%.

- Tourism linked to restored systems: visitors learn about ancient engineering.

4. Afghanistan – UNDP Karez Rehabilitation Project

- After decades of conflict, 150 karez systems were repaired in Herat and Badghis provinces (2015–2022).

- Restored water access for 200,000 people.

- Women-led water committees now manage distribution, enhancing gender equity.

5. China – Xinjiang Karez Conservation

- UNESCO and Chinese Academy of Sciences launched a digital archive of karez maps.

- Solar-powered pumps supplement flow during dry seasons, creating hybrid systems.

- Tourist revenue funds upkeep.

6. Chile and Peru – Andean Adaptations

- Engineers in northern Chile are piloting "neo-Qanats"—hybrid tunnels using modern lining materials (HDPE pipes) and GPS-guided alignment to access deep aquifers beneath Atacama Desert towns.

- Pilot project in Calama reduced reliance on trucked water by 60%.

7. Australia – Outback Experiments

- Researchers at CSIRO are testing Qanat-inspired “subsurface infiltration galleries” to capture ephemeral streamflow in arid Western Australia.

- Early results show promise for recharging depleted aquifers.

Challenges to Widespread Adoption

Despite its virtues, Qanat revival faces hurdles:

- Labor Intensity: Digging and maintaining tunnels requires skilled labor, increasingly scarce.

- Urbanization: Modern infrastructure prioritizes pipelines; Qanats compete poorly for funding.

- Groundwater Overexploitation: If upstream users pump excessively, Qanats dry up—even if well-designed.

- Lack of Awareness: Policymakers often overlook low-tech solutions in favor of “high-tech” fixes.

- Land Rights Conflicts: Ownership disputes over water rights persist in many regions.

Surface runoff captured in wadis

Innovative Hybrid Models: The Future of Qanats

The future of Qanats lies not in nostalgia, but in integration:

1. Smart Qanats: IoT sensors embedded in shafts monitor flow, temperature, and contamination in real time.

2. Solar-Augmented Qanats: Small solar pumps inject water into Qanats during extreme droughts to maintain base flow.

3. Qanats-Aquifer Recharge Systems: Surface runoff captured in wadis is directed into infiltration basins to replenish the aquifer feeding the Qanat.

4. Educational Parks: Open-air museums (like Yazd’s Qanat Museum) combine tourism, education, and cultural preservation.

5. Policy Integration: Countries like Oman and Iran now legally protect Qanat catchment zones—preventing industrial pollution or drilling nearby.

Global Recommendations: Scaling the Qanat Model

To harness Qanats against the global water crisis, we propose:

Action: Implementation

UNESCO & WHO Recognition: Declare Qanats a “Global Water Heritage” with technical guidelines for restoration.

South-South Knowledge Exchange: Create a Qanat Network linking Iran, Oman, Morocco, Afghanistan, and Mexico for training and toolkits.

Microfinance for Communities: Provide grants/loans for village groups to restore local Qanats.

School Curriculum Integration: Teach Qanats engineering in STEM programs in arid nations.

Climate Finance Access: Include Qanat restoration in Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement.

Research Funding: Support universities to model Qanat-aquifer dynamics using AI and satellite data.

Conclusion: Ancient Wisdom for a Thirsty Planet

The Qanat is more than an engineering marvel—it is a philosophy of harmony with nature. It teaches us that sustainability does not require complexity. In an age obsessed with megaprojects and technological silver bullets, the Qanat reminds us that the most resilient systems are often the simplest, lowest-cost, and most deeply rooted in community.

As climate change intensifies droughts from the Sahel to California, from Rajasthan to the American Southwest, the Qanat offers a proven, scalable, and dignified solution. It doesn’t just move water—it moves societies toward resilience, equity, and ecological wisdom.

Let us not bury the Qanat again. Let us dig it out—and let it flow once more!

Further Reading & Resources

- UNESCO. (2016). The Persian Qanat. World Heritage List.

- Molina, M. (2018). The Qanat: A Living Heritage. Springer.

- FAO. (2021). Reviving the Karez: Water Security in Afghanistan.

- Hedges, R. (2005). Water Management in Ancient Civilizations. Routledge.

- [International Qanat Organization](https://www.qanat.org) — Non-profit promoting global Qanat preservation.

Dear Visitor; Please take a look at the list of 50 most visited websites in the world wide web: YouTube, Facebook, google, translate, gmail, weather, amazon, Instagram, cricbuzz, Hotmail, wordle, satta king, twitter, yahoo, yandex, sarkari result, Netflix, google maps, yahoo mail, roblox, whatsapp, NBA, BBC news, outlook, pinterest, flipkart, eBay, omegle, live score, tiktok, canva, ipl, premier league, hava durumu, ibomma, walmart, twitch, ikea, shein, linkedin, home depot, e devlet, lottery, snaptik, cricket, serie a, nfl, spotify, fox news, amazon prime; There is no book publishing related or project management website in this list. We are working hard to bring these important issues to the center of concentration of societies. Please introduce us via social media, share our website with others and help us to make our world a better place to live. Best Regards.

Write your review